Posted by William L. Wunder on Aug 3, 2008

Shareholders of corporations immediately sued to halt their corporations from paying the tax. The various cases were consolidated into Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan and Trust Co. and accepted by the Supreme Court in January 1895. The plaintiffs, represented by William D. Guthrie, George F. Edmunds, and Joseph Choate, claimed that the income tax would induce class warfare that would lead to “communism, anarchy, and then, the ever following despotism.”

Direct Tax and the Uniformity Clause

As for constitutional arguments, the plaintiffs insisted that the income tax was a direct tax- the law’s tax on real property was the equivalent of a property tax, which was a direct tax. According to Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution, “No capitation or other direct, Tax shall be laid, unless in Proportion to the Census or Enumeration…” The plaintiffs claimed that the income tax wasn’t in proportion to the census and therefore it was unconstitutional.

Also, the plaintiffs used the uniformity clause of the Constitution. Article I, Section 8 states that “…all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.” The plaintiffs charged that the vast majority of the affected taxpayers lived in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania. In addition, the tax was not uniform because it was imposed on some kinds of income.

The defense, represented by Richard Olney and James C. Carter, countered with precedent. They maintained that the income tax was not a direct tax. They cited the 1796 Supreme Court decision that upheld a carriage tax, clearly determining that direct taxes referred to only property. Other taxes upheld by the Supreme Court in the past included taxes on insurance companies and the Civil War income tax.

Another argument posed by the defense took on the plaintiffs’ issue of class warfare. According to Steven Weisman, Carter asserted that the best way to preserve private property was to relieve the masses of excessive tax burdens. The poor had paid more than their fair share through consumption taxes and tariffs and the income tax would act as a balance. The income tax would be a safety valve in an era of labor unrest.

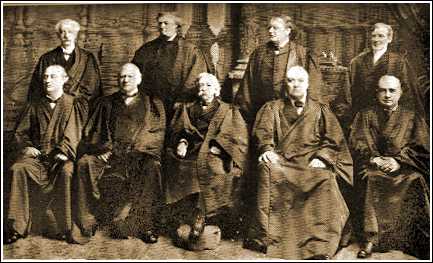

Chief Justice Melville Fuller

The Court decided the case in April, a Court that believed “property was sacrosanct,” and “economic regulation was taboo,” according to writer Burt Solomon. Chief Justice Fuller, writing for the 5-3 majority, declared that income taxes on real estate was a direct tax and therefore unconstitutional. The majority also discarded the tax on interest from municipal bonds as an infringement on the states. However, with one justice absent, other issues in the case split 4-4 and the case was retried.

In May, with a full complement of justices, the Supreme Court threw out the entire Wilson-Gorman law by a 5-4 margin. Fuller, again for the majority, wrote that the unconstitutionality of the income tax on real estate scuttled the whole law, despite the possibility of some taxes, like wages, being constitutional. Dissenting, John Harlan stated that it was a dangerous precedent in ruling income taxes unconstitutional- it could open society to social unrest.

Both sides in Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan and Trust Co. feared that unrest if they didn’t prevail. And both couldn’t agree on the definition of a direct tax as written in the Constitution. What did become apparent, according to Harlan, was that a constitutional amendment allowing income taxes would be needed. That was for the future- the Sixteenth Amendment.

Sources

Solomon, Burt, FDR v. The Constitution, Walker: New York, 2009.

Weisman, Steven R., The Great Tax Wars, Simon and Schuster: New York, 2002.

Also see:

Today in History: Income Tax Ruled Unconstitutional in Pollock v. Farmers Loan Trust Co. | Tax Foundation | April 8, 2013

Supreme Court Case Pollock v. Farmer’s Loan and Trust Co. 1895